Stat of the Match: Liverpool 2-0 Manchester City

Liverpool did something against Manchester City which they never did under Jürgen Klopp. A lesser stat also highlighted elements of Arne Slot's tactical plan

Is there any team that can stop Liverpool this season? The reigning champions of Germany, Spain (and Europe) and now England have all been sent home from Anfield, goalless and beaten. Manchester City are the latest to be swatted aside, defeated 2-0 on Sunday.

The score line genuinely flattered Pep Guardiola’s men. Trivia revealed by various Opta accounts proved the point; Analyst noted it was only the second time City have conceded at least three expected goals in a Premier League game (since records began), while Joe revealed it is over 14 years since they had to wait so long to take their first shot in a league game.

The headline on a BBC article about the game read ‘How Liverpool mixed best of Klopp & Slot to beat Man City’ citing the “chaos then the control” they brought. As the Reds used long passes to quickly turn around City’s ageing, creaking backline, often after turnovers, the notion was not without merit. It overlooked a vital difference between how Liverpool beat the Citizens under their former manager and current head coach though.

Pass success rate can be used as a very - very - basic method of assessing control. If a team is able to complete a high proportion of them, it’s reasonable to say they played the game on their terms. In this sense, there was a very marked shift from Jürgen Klopp’s victories in this fixture.

Liverpool completed 81.9 of their passes, per FBRef. If you sort a table of the Reds’ pass success rates against Guardiola in the two main competitions since 2017/18, highlighting the wins reveals a clear demarcation.

Klopp’s victories occurred with Liverpool’s five lowest pass completion percentages from clashes with the Citizens, all at least five per cent shy of what Arne Slot’s side mustered. At the top of the table are two of their heaviest defeats. In terms of this metric and shots, the most recent game was similar to the 1-1 draw in March, though the non-penalty expected goal difference stands comfortably above anything from the preceding seven seasons.

There was another statistic which shows a difference with several of the five Klopp wins on the chart. Liverpool did not score from an Opta-defined fast break (counter attack).

Such goals have proven invaluable in the past. The Reds’ only goal in their 1-0 win two years ago came on the break, as did their opener in the 3-0 Champions League victory at Anfield. A period of three goals in nine minutes which took the match away from the Cityzens in the unforgettable 4-3 triumph was kickstarted by Roberto Firmino converting a counter attack too. Simplistic shorthand or not, it is a slight misreading the performance on Sunday if describing Liverpool’s style as ‘chaos then control.’

There was one other statistic of interest. Not because it had any bearing on whether either side deserved to win, but more because of how it indirectly illustrated the pressure under which City wilted.

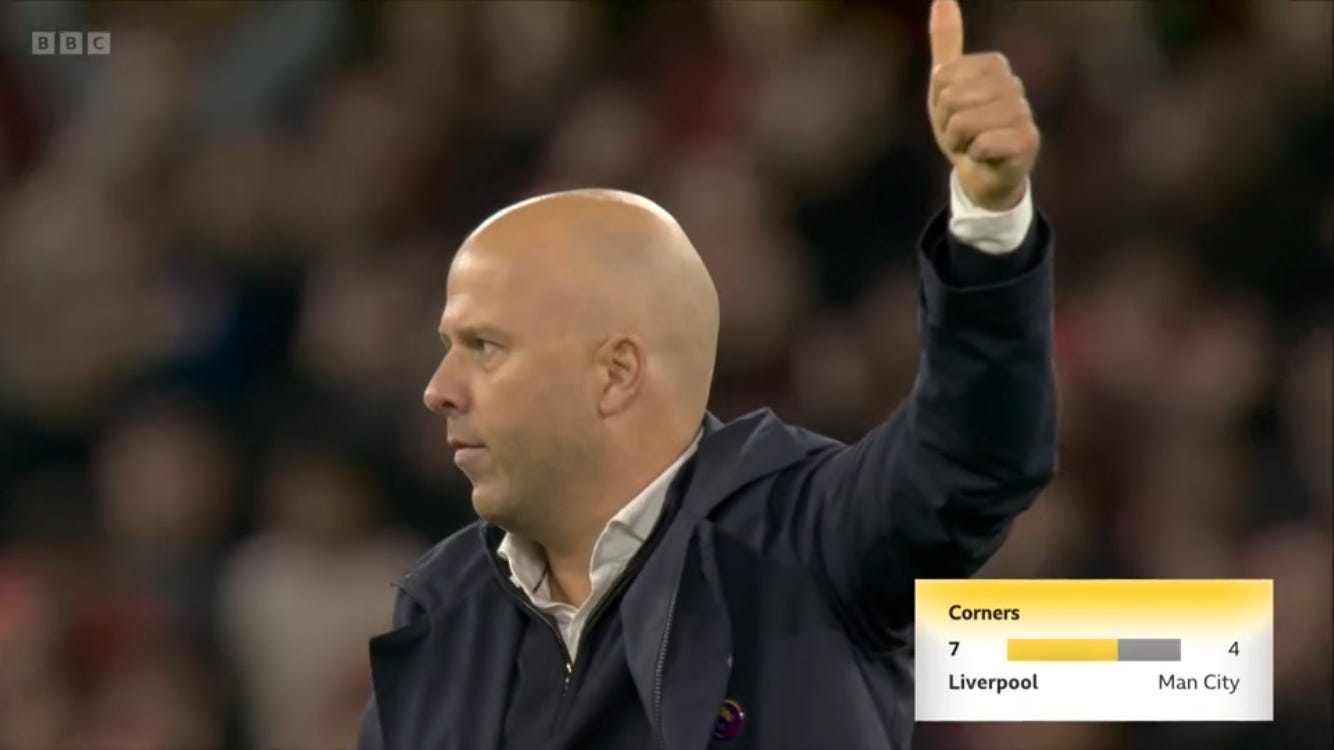

The order in which Match of the Day share stats over their post-match interviews seems odd in the advanced data era. We see possession, shots, on target, corners and then expected goals, before bookings. Promoting corners over xG seems absurd, though in this instance the former did show something notable.

City do not give away many at all. Corners are often symptomatic of a lack of control, as they occur thanks to blocking or saving shots, closing off a winger’s path into the penalty box, that sort of thing.

The perennial champions conceded just 2.6 per game in 2022/23, a whole corner fewer than the next best sides. While they rose above Arsenal on this metric last season, their average of 3.5 a match meant the threat level remained low.

Ahead of their trip to Anfield, City had allowed just 29, or 2.4 per game, this term. Newcastle mustered five, Chelsea four, nobody else had produced more than three. Liverpool had seven, with all-but-one of them occurring in a 40 minute spell which started in the 11th minute.

The first came from Matheus Nunes blocking a Trent Alexander-Arnold pass. It led to the chance from which Virgil van Dijk struck the woodwork.

Six minutes later, with Liverpool having taken the lead in between, Mohamed Salah was almost clean through, only for Nathan Aké to recover well. The same pair were involved in a similar corner-generating move in the 33rd minute, and again in first half stoppage time.

From the first of this trio, van Dijk had another header, with Opta deeming it a big chance; no argument here. Alexander-Arnold then had off target efforts following the next two, though he did hit the woodwork after the second corner was partially cleared. There was an instance of Andy Robertson winning a corner on the opposite flank, roughly 150 seconds after van Dijk’s big chance, but Liverpool were clearly making everything they could out of Salah’s ability to challenge defenders on the right.

The first of the pair in the second half did summon memories of Klopp’s Reds, as Liverpool broke quickly. A great pass from Robertson found Cody Gakpo, though the goal scorer’s shot was blocked by Nunes to send the ball out of play.

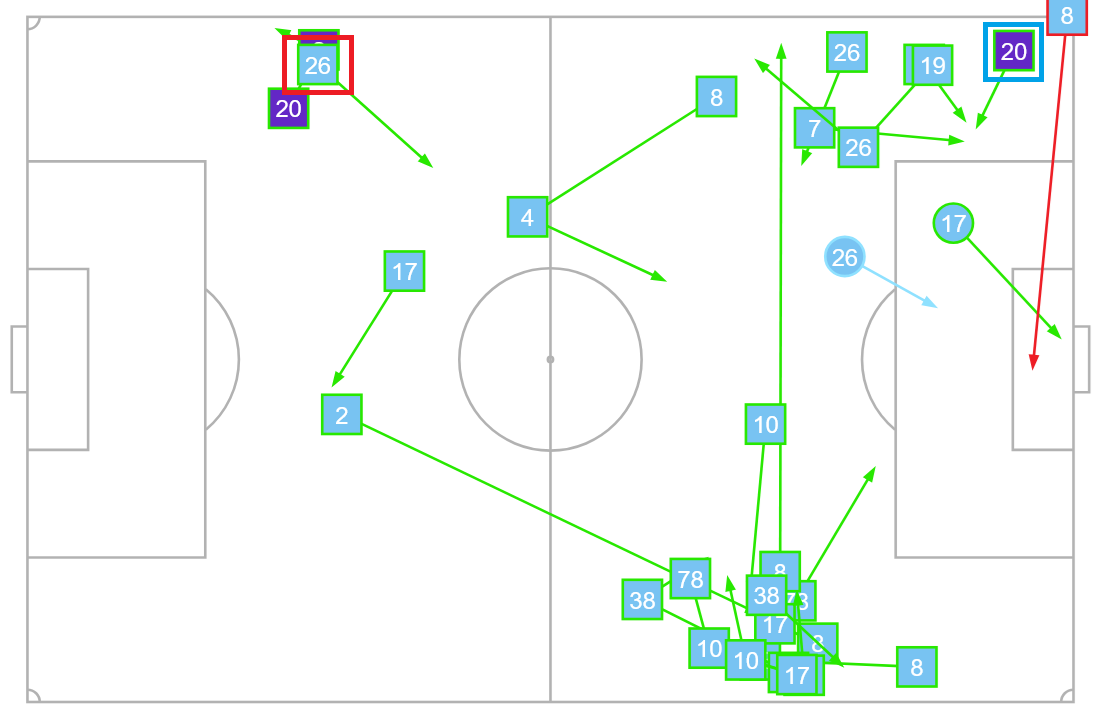

It will have been the move for the final corner which likely pleased Slot most of all. Granted, it occurred across the closing minutes of the match, by which point City were a beaten side, begging for the sweet relief of full time.

Even so, Robertson (highlighted below in red) regained possession at 88:54 and one Bernardo Silva pass aside (in the blue square), the visitors did not have control of the ball again until Darwin Núñez was offside at approximately 91:58. In that time, Liverpool had two shots either side of the corner in the image at the top of the page.

Digging beyond raw corner numbers can tell you quite a lot about a game after all. Maybe the BBC should have gone with ‘control and corners’ for their assessment.